Baptiso to Immerse

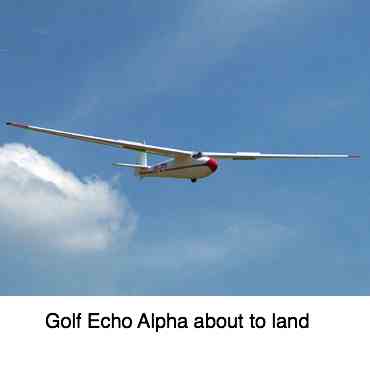

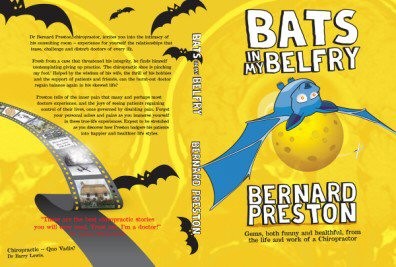

Baptiso to Immerse concerns a sublime day of flying in Bernard Preston's glider; it is chapter 16 from Bats in my Belfry.

“Show me a family of readers, and I will show you the people who move the world.”

Napoleon Bonaparte

This page was last updated by Bernard Preston on 22nd July, 2019.

I was first baptised, aged three months, into a pagan family so it didn’t really count. The bishops didn’t approve of my theology when, at the second visit to the font I was baptised, aged nineteen, into Christ. The third time? In my dotage, into humility. It happened one Saturday like this.

I woke early and went out into the garden for a sweet pee. A half moon and Venus were in close proximity, brilliantly etched against the eastern sky, greeting each other as it were. A scattering of cumulus, brilliantly white in the early dawn stretched westwards, fading as the clouds further west still desperately avoided the probing rays of the as yet invisible burning sun. All was silhouetted against a blue-black sky. Could be a good day, I mused.

Glider pilots are inveterate optimists, gazing hopefully into the heavenlies every Saturday morning. It was one of those magical moments that only the ‘early to bed, early to rise’ devotees can enjoy. By the time Helen rises from her beauty sleep the best part of the day is already done! The crisp early African morning has a beauty that never seems to cloy, and in me there is a deep appreciation of a life that does not dull, despite ten thousand similar dawns. No, today’s was different. I couldn’t recall even one that was vaguely like it. A stroll in the garden definitely beats the toilet for relieving yourself first thing in the morning, I thought, with only a few Hadedas to squawk at me. The Cymbidiums were beginning to spike and they needed the extra urea, I reasoned.

"Success is not the key to happiness. Happiness is the key to success."

- Albert Schweitzer

I picked up the East Griqualand Herald at the gate, going through the daily struggle; shall I read the Good News or the Bad News first? Three mugs of tea later both my soul and my need to keep up to date with world events were satisfied and I started preparing for what was to be the day. I was still blissfully ignorant, of course. Ahead lay a day that would remain indelibly etched on my mind for the rest of my life. Batteries for the radios were on charge, hats packed, tea and some home-made bread were all in readiness. I hurriedly pared a cucumber for fibre and sliced a tomato for my prostate, all in vain. None would be eaten.

Had I been able to look into the crystal ball I would have saved myself the trouble. It was just as well that I had fully charged those batteries, though. I was going to need them.

It’s a funny thing, the earlier I rise, the later I get going. I was late in arriving at the gliding club that day but then I did have to spend a few hours at the clinic. My patients that morning included an elderly lady with a very painful neck after being savagely beaten by intruders, a couple of routine sore backs and a young man with a fracture in his spine after a car accident.

I updated all the day’s files, so that I could leave the clinic with a good conscience, and completed the detailed report for the lawyer. He was determined that his client would be fully recompensed by the Road Accident Fund, and his cut too of course which, in the gospel according to Abba, makes the world go round: Money, money, money… Do we acquire our fortunes or do they ensnare us?

It was not to be a routine day, either at the clinic or later in my favourite pastime. I should have guessed right then that something remarkable in the sky was awaiting me. The dash to the club was also memorable. I was late, and now even further delayed.

The material expressed on this page is gleaned from the nutritional and environmental literature; it is clearly referenced. A plain distinction is made between the author's opinion and that which is scientifically proven. When in doubt consult your health professional.

To suggest a correction or clarification, write to Dr Bernard Preston here. Contact.

As I approached the airfield I was stopped at the site of a minibus taxi lying on its side, dead bodies strewn about the road. Fortunately the ambulance and the police had already arrived. Unable to stop myself staring at the carnage, my mind travelled down an old familiar track, having difficulty taking off the Chiropractic hat and putting on my soaring cap: The so-called road accidents that brought me so much work should really be named road trauma; they are after all no accident, being in the main highly predictable and it is going to take rather more than a few feeble clichés like ‘Zero tolerance’ that soft-headed politicians like to promote to stop the terrible suffering on South African roads.

I allowed my mind to drift as I drove on to the club, trying to forget my responsibilities as a chiropractor and the mayhem I had just witnessed, which was perhaps a good thing. That mind was going to be extremely focussed for the rest of the day as I struggled to stamp my authority on the elements, denying them their natural inclination to punish those who dare to defy them.Late arrivees are sent straight to the winch that launches our gliders into the sky and so I did my penance. ‘Don’t apologise,’ said Carl, one of our best instructors, with a smile. ‘We love it when you get here late. Then there’s no fuss about who is going to be on the winch. You!’ he finished, poking me on the chest. Being stuck on the ground is not a pilot’s idea of fun.So the next couple of hours were spent launching my friends’ gliders and, for once, events turned out well for the latecomer. The gliders all fell out of the sky as the elements retained the upper hand. An early launch would have been in vain. I smirked, watching a street of clouds developing, reaching out towards the north-west. This might be a good day yet.

Finally the next winch driver arrived. ‘There is only very strong sink, Bernie,’ Shirley said. ‘Don’t stray too far from the airfield or you might find yourself out-landing!’ Glider pilots are not all male. There are also a few women, equally intrepid or mad, according to your viewpoint, smitten by soaring.

‘When there’s strong sink, Shirley, there’s also strong lift. I’m going to find it!’

‘Yes, yes, Bernie, the eternal optimist, always arrogant. I give you no more than ten minutes aloft.’ Shirley smiled at me as we swapped places and I drove over to the clubhouse to haul out my ancient Ka6 from its hangar. A new member who wanted to please lent a helping hand.

In fact, I was wrong. It was Shirley’s husband in his beautiful ASW 15, a fibreglass ship that stood out in sharp contrast to my old plywood crate, who found the lift.‘Turn round, Bernie, and fly straight back to the launch point. There’s a beautiful blue thermal∗ over the copse of Wattle trees,’ Graham called on the radio from aloft while I was preparing for take-off. Thermals are often marked by a cloud but blue thermals were found simply by luck. Graham had the first dip into the lucky-packet. I craned my head, scanning the sky for his glider from my tiny cramped space in the cockpit, feeling a tiny crick in my neck. Ah, there he is, I could see Graham above my head banking steeply and, even from the ground, I could see that his glider was climbing fast. Hooray! Big boys and their toys, I taunted myself, recognizing a still present need for childlike excitement.

Shirley gave me a beautiful launch with the needle hovering around 90kph and, when I pulled the release cable, I found myself at 1400 feet agl (above ground level). The altimeter, of course, gave me the height above sea level, 6,000 feet asl. I checked my speed and turned sharply back to where I had seen Graham’s glider. He was already at least 2000 feet above me, but there was very strong sink all the way back to the invisible thermal. I was sinking fast and gave a groan when I found myself at 600 feet above ground and having to prepare for a landing circuit. Then the variometer started to sing and I felt the big hand smack me in the seat of the pants. I waited the customary three seconds so as not to fly right through the thermal and then banked steeply, using the ailerons and adjusting the rudder pedals. The first turn saw me climb a hundred feet or so and my groan turned to a shout of exultation. Up, up and away. Within fifteen minutes my glider carried me all the way to ten thousand feet above sea level in one beautiful thermal.

I was joined by a pair of giant Secretarybirds. Like gliders they are stiff and ungainly on the ground but, with a wing-span approaching one and half metres, they are astonishingly elegant in the air. From the vantage point of my cockpit I watched them playing the giddy-goat, fooling about with each other. Thermalling one moment just off my wing tips and then diving and swooping, by dropping their legs for airbrakes in a most odd manner, they were quite unperturbed by their giant white companion. I sighed, supremely contented. Eventually the birds, bored of my company, dived and I watched them land in the centre of the runway nearly two kilometres below, disturbing proceedings on the ground. It was a divine moment.

Cloud base was another 2,000 feet above my head but the ceiling of our airspace over the club was restricted to 10,000 feet above sea level. I was not allowed to soar any higher here. I watched Graham turn and fly over Lake Msimang, leaving the restricted area and heading further north towards the great dam wall. He hit the strong sink and I decided to go further south towards a promising looking cloud with a dark-grey underbelly. It was the right decision. Graham never got back to 10,000 feet and we had to shelve our plan to investigate the Midlands, west of the airfield, together. I too hit the sink but, on the far side of the lake, over Mount Aston, having sunk to 8,000 feet I found the thermal of the day. I was now outside the gliding window that had restricted me to 10,000 feet and my glider soared even higher into the sky. I gave a little shiver, a pleasurable frisson of anticipation. Or was it just the cold? At launch the cockpit thermometer had read forty-two degrees Celsius in my little greenhouse. I watched as it plunged down to ten degrees, a jet of cold air turning my nose red. I stuffed an old handkerchief into the aperture in the Perspex canopy, pulled my cap a little deeper over my head and wished I had a scarf.‘Yankee Zulu, this is Alpha X-ray. What’s happening, Graham?’ I called on the radio. (All aircraft are given three letters for a call sign. Mine was GAX or (Golf) Alpha X-ray. Since all gliders are given the prefix ‘Golf’ we tend to drop the first Golf: Graham was GYZ or (Golf) Yankee Zulu.

‘I’m struggling, Bernie, you had better make your own plans.’ I could see him far below me losing out to the cold sinking air near the dam wall.

I had only once been above ten thousand feet so I cruised happily around the sky, contented yet keeping a sharp look-out out for other gliders. There were none. I had the stratosphere to myself, shared only by the odd Airbus on its way to Cape Town or Bloemfontein.

More threatening was the massive grey dome of cloud, now only a thousand

feet above my head, inviting me into her bosom. Thirty seconds in that

great sucker and I would be dead, having lost all orientation. I wasn’t

instrument rated, nor was my glider and, in any event, cloud-flying in

gliders is strictly forbidden in South Africa. The canopy of my glider

began to shudder alarmingly in the powerful lift so I hurriedly left the

thermal and its dangerous cloud-top, deciding this was the day to

investigate the meandering oxbows of the Elephant River north of the

dam. Could I reach Liddletown? I had never flown that far from the

airfield and it suddenly dawned on me that this could be the day for my

first true cross-country flight. A street of clouds beckoned,

seductively, fifteen kilometres to the west. Turning your back on the

airfield for the first time and flying out into the great unknown is one

of the momentous highlights of soaring, never forgotten. That decision

is never taken lightly, the repercussions potentially fateful. My inner

equilibrium disturbed as I travailed with the idea, I decided that an

important radio-call was in order.

‘Shafton Ground, this is Alpha X-ray,’ I called the airfield.

‘Go, Alpha X-ray,’ came back the reply from the duty pilot of the day.

‘Wind direction and strength, please.’

‘Less than five knots from the west,’ came back the reply.

‘I’m at 11,000 feet and going for a walk-about in the direction of Nottingham Forest,’ I called back. It was important to keep him informed in case of misadventure.

‘Enjoy!’ came back the reply. I could hear the envy in his voice and I pinched myself. Was this really happening? Was it just a dream?

In between the banks of clouds where the lift is found – every cloud marks the top of a thermal – are great troughs of cold sinking air. I glanced out to the west at the beautiful street of clouds at least 15 kilometres away. Could I make it? Flying into a gentle headwind would make the return flight easier and I made the critical decision: Go! Excitement and, in equal measure, fear teased me; I couldn’t believe it was happening. Half way to the bank of clouds, having lost two thousand feet, to my relief I flew through another blue thermal. As I banked steeply to maximise the lift I found myself staring down the wing at Astonhouse where I had spent so many happy years teaching science. Nothing much had changed. Memories threatened to swirl around, taking the squash team on tour to Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, happy hours spent coaching sport on the fields I could see far below me, but I quickly dismissed them. Flying is unforgiving for those who are unable to concentrate on the job at hand. I levelled the wings and set my sights on Nottingham Forest and the bank of clouds ahead. The thickly wooded terrain far below me looked distinctly unfriendly. I followed the old highway carefully: it’s very easy to get lost on a cross country flight although Lake Msimang and the Tollroad further north, off my right wing, were still clearly visible. More sink disturbed me but I was still at 9,000 feet when I reached the bank of clouds with a sigh of relief and climbed all the way up to cloud base, now at 12,000 feet above sea level. Oh, this was good. Life was good. I was at least thirty kilometres from home and nearly three kilometres above the ground lying far below me.A new voice came booming over the radio, chattering with another club glider, the unmistakable accent of a Yorkshire Dales sheep farmer who flew out of Pinnacles Gliding club. Pinnacles? Could I reach Pinnacles from here?

There are three tasks that are important milestones for every glider pilot. One of them is easy, a 1,000 metre height gain that every pilot will achieve within a few months of going solo. I had probably done that a hundred times, though none had been registered because nobody routinely carries a barograph. The five hour endurance flight was difficult enough but it was the fifty kilometre cross-country flight out of Shafton that had only been done a few times. The terrain and the conditions just weren’t suitable. Pinnacles? Could I really reach Pinnacles? My stomach was turning, churned with equal measures of excitement and panic. Later, after my baptism, my friends told me how they had joked over the anxiety heard so clearly over the radio. Yes, it was scary but, drinking so deeply from the cup of life, the forests far below held no terror.

‘Whisky Echo, this is Alpha X-ray out of Shafton Gliding Club. I’m at Nottingham Forest at twelve thousand feet.’

‘You’re far from home, Alpha X-ray. What are your intentions?’ I had met the Yorkshire man before, his voice unmistakable, the accent recognized world wide by lovers of cricket. Geoff Boycott is an icon.

‘Tom, is that you, in Whisky Echo?’

‘No, it’s not… it’s…’ His radio signal was broken by static and I couldn’t hear him clearly.

‘Can I reach Pinnacles from here?’ I asked.

‘Yes…’ More broken patter. Damn radios, just when I really needed to hear him clearly. I was panicky. Would the wise pilot turn and head back for the safety of the womb? Should I press on for my first 50 kilometre cross-country flight? More travail.

‘What’s the best route to Pinnacles, Tom?’ I called again, not knowing that I had got his name completely wrong and was making an ass of myself over the airway for fifty kilometres or more, in every direction. There was nothing wrong with my radio.

‘Fly towards… Mooi Plaas and then go directly along the Toll road to Pinnacles.’

‘You’re very broken up, Tom. Which way to Mooi Plaas? Do I fly to the Toll road or do I fly via Swartberg?’

I was scared. In retrospect I was possibly even experiencing some oxygen debt at that altitude. Steadying my anxious mind and controlling my fear, I pondered a moment. Stupid questions, I would have to choose myself one of several routes. It was no earthly good, or heavenly either, asking him to recommend a route. I scanned the sky. Over Swartberg I spotted a promising cloud. That was the way. In actual fact, it would have made no difference. With my height a straight glide would have taken me to all the way to Pinnacles but I didn’t have the confidence to do that.

Shafton airport ground control was out of my range now but I could still hear the chatter from several of my friends’ gliders in the air. I relayed my intention to fly on to Pinnacles and would they please prepare my trailer for a retrieve? ‘Yankee Zulu, Alpha X-ray is at eleven thousand feet and pressing on to Swartberg and Pinnacles.’ All I got from Graham was a buzzing on the radio. He was too low for me to hear his reply.

I set my course for the nearest cloud and increased my speed to over 120kph for the sink that I knew I would enter, immediately I left the thermal; and so I did.

Newsletter

Our newsletter is entitled "create a cyan zone" at your home, preserving both yourself and Mother Earth for future generations; and the family too, of course. We promise not to spam you with daily emails promoting various products. You may get an occasional nudge to buy one of my books.

Here are the back issues.

- Lifestyle and ideal body weight

- What are ultra-processed foods?

- Investing in long-term health

- Diseases from plastic exposure

- Intensive lifestyle management for obesity has limited value

- A world largely devoid of Parkinson's Disease

- The impact of friendly bacteria in the tum on the prevention of cancer

- There's a hole in the bucket

- Everyone is talking about weight loss drugs

- Pull the sweet tooth

- If you suffer from heartburn plant a susu

- Refined maize meal and stunting

- Should agriculture and industry get priority for water and electricity?

- Nature is calling

- Mill your own flour

- Bake your own sourdough bread

- Microplastics from our water

- Alternative types of water storage

- Wear your clothes out

- Comfort foods

- Create a bee-friendly environment

- Go to bed slightly hungry

- Keep bees

- Blue zone folk are religious

- Reduce plastic waste

- Family is important

- What can go in compost?

- Grow broad beans for longevity

- Harvest and store sunshine

- Blue zone exercise

- Harvest and store your rainwater

- Create a cyan zone at your home

I could see the road meandering along towards Mooi Plaas, and a series of beautiful lakes to the west mirrored the harsh African sun. I had never seen them from the air before, and now the Drakensberg was clearly visible to the west, silhouetted against the hazy sky.

A swift glance took in the whole sweep from the magnificent Sentinel in the distant north, to Giants Castle and the Rhino in the south. That’s all that my anxious mind would allow me to indulge in and I focused again on the task at hand.

Swartberg was below me and surely the ugliest village in South Africa, ironically called Mooi Plaas, lay just ahead.

With growing confidence I passed the Toll, free for me, and pressed on towards Pinnacles, now only 20 kilometres away. I could see the roofs glinting in the harsh late summer sun.

‘Keep your speed up, Alpha X-ray, at least 100kph. By the way, it’s Fred, not Tom. Where are you now?’

Fred’s radio was suddenly clearer. I heaved a sigh of relief, relieved at the encouragement from the vastly experienced pilot. Yes, I was going to make it.

‘Thank you Whisky Echo, Fred… I’m at 9,000 feet with the Microwave towers on Piggott’s Peak just off my left wing.’

‘Can you see the runways, Alpha X-ray? They are straight ahead of you.’

I scanned the terrain ahead. Secretaries’ Dam was clearly visible to the west of the town and there right ahead I could see the X of two runways clearly marked at the airfield, though they appeared tiny from my height, hardly recognizable. I was determined to make certain of the full 50 kilometres for my Silver C so I flew past the airfield and over the picturesque dam with its towering cliffs.

Below me I spotted Fred’s Twin Astir as he waggled his wings. He had sighted me at almost the same moment. It was a relief and I turned back to the airfield, preparing to land on the unknown runway. I took a good look, announced my intentions on the radio and started to sideslip with airbrakes fully open to lose height. I was climbing! What was happening? I realized that I had flown accidentally into another blue thermal; a new thought slipped uninvited into my mind. Could I make it home again? Could I go through all that again, twice in one day? I closed the airbrakes and concentrated on centring in the thermal. The variometer needle started banging on the top stop and, before long, the altimeter needle started winding its way steadily back to 11,000 feet asl. Never had I experienced such powerful thermic conditions.

‘Whisky Echo, this is Alpha X-ray again. What are the chances of me flying back to Shafton?’ I asked. ‘I’m back at 11,000.’

‘If you can make it back to Nottingham Forest, it’ll be a cinch,’ called Fred. I realized my flight would be downhill from the Forest, located on the edge of the escarpment, at about 6,500 feet, to Shafton which was at only 4,600 feet asl. Would the same street of clouds that had brought me unerringly to Pinnacles take me home? I looked south, searching for over-development of the clouds and worried about the mist that would creep over the escarpment if the wind had, unbeknown to me, veered to the south.

‘Shafton gliders, this is Alpha X-ray over Pinnacles at 11,000 feet. Is anyone receiving me?’ I called home, more than fifty kilometres away, needing information.

A faint reply: ‘Go, Alpha… this is… Uniform…’ It was broken up but I recognized Andrew, our CFI’s voice and the call sign of our double-seater.

‘Wind direction at Shafton please, Uniform Bravo?’ I loved the old double-seater training glider that Andrew was instructing from. It was the same glider that had taken me solo more than ten years ago. I could hear him calling the duty pilot at Shafton and he then relayed the information back to me.

‘Still from the west, Alpha X-ray.’

‘Thanks, Andrew. Alpha X-ray is going to attempt an out and return.’ I said my farewells to Fred and the Pinnacles club and set my sights on the Toll road that would lead me home. The hot tarmac was still giving birth to bubbles of hot air, forming the same street of clouds that lay scattered along the highway. It wasn’t long before I was again soaring high over Mooi Plaas, still the ugliest village in East Griqualand. Nothing had changed. I caught another boomer and then flew straight on to Nottingham Forest. The lakes on the Little Mooi had a strange foggy appearance that gave an illusion of smoke, with the clouds reflected in the water, and I pressed on with the wind now at my tail. Below, the whole vista of Shafton rapidly opened, with Lake Msimang the beacon that would guide me home. It was a straight glide, over the forests of indigenous Yellowwoods and exotic Pines that terrified us, stopping all foolish notions of attempting long cross-country flights out of Shafton. Being forced to land in a forest is often fatal. I slowed down in the lift when my variometer notified me that I was in rising air and increased my speed in the troughs of cold sinking air, arriving back at Shafton still 5,000 feet above the airfield.‘Welcome home, Alpha X-ray,’ called my friend Carl, from his mobile radio. ‘We’ve got the reception committee ready.’ I could see the club bakkie parked where I would land. I opened my airbrakes and searched for some sinking air to circle in. The altimeter wound rapidly down and I prepared to do my circuit, concentrating on the task ahead. Most glider accidents happened on landing and launching and I was exhausted after the draining flight. Concentrate, Bernie. It was an uneventful landing, as I flew just a metre above the ground, losing speed until the glider stalled gently onto the soft grass runway.

Gliding

Gliding is one of the most profound and enjoyable activities that I, Bernard Preston, have ever been involved in. It's not a sport for everyone, obviously. But Baptiso, to Immerse, combines the immense sense of awe at soaring with eagles and knowing the God who dwells within.

Baptiso to Immerse

As I opened the canopy the welcoming group of pilots surrounded my glider, helping me out from the cramped quarters as I loosened the parachute. Their solicitousness completely deceived me. They’re so nice, I thought, as they helped me onto the back of the bakkie, with much back-slapping and hand-shaking. ‘We’ll put your glider away for you!’ someone cried. What a fool, I was completely deceived by their smiles and guffaws, my tired mind not registering that we weren’t driving to the clubhouse for the first celebration frosty but to the farm dam.

‘Hey, what’s happening?’ Strong arms grabbed me and moments later I was swung high in the air, boots and all into the dam. I came up gasping for air, with Carl laughing in the water next to me and the rest of the crew cheering from the shore.

‘That’s the Afrikaner tradition,’ he said, wiping some weed out of his hair, ‘just in case you get too cocky!’ It was only later that I discovered that an out and return to Pinnacles hadn’t been done for 20 years, and then in a fibreglass ship with a glide ratio of over 1:40. It was an important lesson for me. Cockiness and over-confidence mostly is what kills glider pilots.Next morning I woke late, a bear with a sore head, and it had nothing to do with too many frosties or baptisms in farm dams. I couldn’t turn my neck to the left and looking upwards gave me sharp stabs of pain in the neck. All that craning of my neck, looking for other gliders and clouds, all the stress and anxiety was concentrated in a small joint at the base of my skull. I palpated the area, feeling the spasm in the tiny muscles that control the upper cervical spine movements and the fixated joint that was causing it all. Damn! Helen brought me a packet of frozen peas wrapped in a tea-cloth and I gingerly moved my head from side to side, knowing that a self-employed chiropractor needed something far more life-threatening than a stiff neck to keep him away from work. If I was a state employee, I would certainly have taken three days’ sick leave, but there was no escaping the salt mines for me. Fortunately I knew that the best treatment for a torticollis was at hand. Scott would adjust the nasty subluxated joint that was giving me a throbbing headache and the stiff neck. Having said that, a really painful neck can be many times more painful than even the worst low back pain.It took several weeks for me to return to planet Earth from Cloud Nine. Fortunately, just by closing my eyes I can, and still do, revisit that epic day whenever I choose.

Enjoy it on your Kindle or tablet.

CHRISTIAN HYPOCRISY

Sadly the subject of Christian baptism has split the Protestant

Church right down the centre. It's an important doctrine; but to make

it so central that brother is totally at odds with brother? To immerse, or not to immerse, that is the question.

Bernard Preston CHRISTIAN HYPOCRISY ...

Update: Carl began to lose weight. Once or twice he spoke to me of headaches he was suffering from. However, he never consulted me, so I never had the chance to examine him. Perhaps just as well, as the doctors he did consult complete missed the brain tumour until it was too late.

So many fond memories, we remember and won't forget you, Carl. One of the gems of this world, a true friend. How many true friends can you count? More than the fingers on one hand? You're lucky.

Anti Cancer is the remarkable story of one man's struggle with brain cancer. An amazing man, a courageous and successful story... but why not change before the cancer strikes? Anti Cancer ...

Latent heat fusion

In the life of every Christian there once came a moment of decision; some compelling reason that could no longer cause one to continue resisting the call of a loving God. Mine was the discovery of the importance of latent heat fusion; without it life on earth would be impossible; and that, for me, a life without God was equally non-nonsensical. Baptiso to immerse is a just a play on words.

Interestingly, contrary to popular belief, there are more scientists who believe in God than those from the philosophical fields; just read some of the works of Isaac Newton, Galileo, and Einstein for example.

- Go from BAPTISO TO IMMERSE to Latent Heat Fusion, the principle that brought Bernard Preston to faith.

INTERESTING LINKS

- Return to BATS IN MY BELFRY homepage …

- The cure for Writer's Cramp. Every writers Six Ds

- PARSLEY BENEFITS ... do you bruise easily?

- Just for laughs

Bernard Preston

Playing out the latter stages of life, on his 69th orbit of the sun, life has been very satisfying for Bernard Preston. Now he's try to do his small part to ensure his children's children can enjoy the beauties of the great outdoors that have meant so much to him. Writing stories like Baptiso to Immerse is one of his many pastimes.

Backyard permaculture is one of those many hobbies; like his hens he's into his greens. Do you think the eggs from these beauties are rather different to those reared in cages? Just the extra choline makes them special; the average Western diet has at best 50% of the recommended amount of this vital B vitamin.

Did you find this page interesting? How about forwarding it to a friendly book or food junkie? Better still, a social media tick would help.

Address:

56 Groenekloof Rd,

Hilton, KZN

South Africa

Website:

https://www.bernard-preston.com